Find a trainer, any trainer, and ask them about exercise program design. Most likely the individual you have chosen will hold beliefs regarding program design that are reflected in the breakout below. These archetypes: the perfectionist, the simplifier, and the artist, each represent a distinct approach, and mindset, regarding exercise program design.

Surely other possible beliefs exist. Humans are rarely “this” or “that”. In fact, many trainers reading this article will surmise themselves to be somewhere between at least two of the archetypes – a truth that accurately reflects the “it depends” mindset of successful coaches in this industry. As this article will highlight – a blend of these three archetypes is necessary to optimize the program design process.

Still, most fitness professionals, if asked to choose, would identify as either the perfectionist, the simplifier, or the artist.

You will notice the omission of the “day-of-programmer” – the sort of trainer who makes up their client’s workouts each morning as the sound of TsssssSSSkr-Pop highlights the opening of their morning BANG energy drink. With a pen in one hand and caffeine in the other – these individuals rely on generalized knowledge, previous experiences (as discussed in this article), and a mild urge to “mix things up” to guide their decision making.

We also will not consider the “anti-programmer” – the type of person who would go skydiving without making sure their backpack is packed with a parachute instead of their high school gym uniform and textbook covered in brown paper and marked up with those Sharpie “S’s” we all learned to draw between 1998 and 2007. Going into a training session in 2021 without a training program (even the simplest one) is unacceptable.

Within a margin of error, nearly all successful trainers approach program design as one of the following:

THE PERFECTIONIST

Program design is intimidating and causes significant anxiety in the trainer. What could be a process that takes no more than a half-hour often devolves into a weekend long tug-of-war match in their minds. The program must be perfect, align with the proven principles of the field, and be individualized top-to-bottom to reflect the client.

This person could be an avid student of industry pros with a wealth of knowledge and experience who regularly finds themselves second-guessing and late-night Googling to justify their programs.

Similarly, a newly minted fitness professional caught in paralysis by analysis, frozen by the pressure of designing the right program for the right person, fits the description too.

THE SIMPLIFIER

Program design is easy – it is as simple as adjusting your pre-designed template to your client’s goals and abilities. There is no need to overcomplicate the planning process when the client is just looking for a challenging workout that delivers results. Within a few hours each month, this trainer can change every client’s programs and keep the train rolling.

This fitness professional is business-savvy, understands the value of simplicity for scaling themselves. So long as they honor science and client-specific variables – there is no need to get caught in the minutia. The general client needs generalized programs with subtle, but specific, individualizations. Leveraging templates, client avatars, and other optimization techniques – this trainer is built to expand.

THE ARTIST

Program design is fun and intriguing. It is an opportunity for the trainer to flex their unique approach, their commitment to continuing education, and their ability to “keep the sessions interesting”. Experimenting with various principles and theories makes sessions seem random and new to the client while being firmly based upon hours of private study on behalf of the trainer.

This person is likely to wake up on a random Monday morning and decide that a different periodization model, a different loading schematic, or the addition of accommodating resistance is all that is missing from their client’s path towards success. Often “lost in the sauce” – these trainers have a tendency of getting in their own way and causing plateaus by ignoring the benefits of progressive overload over time.

EXPLORING THE SPACE

Each of these archetypes represents a real trainer in our industry. They represent YOU, the dedicated fitness professional who wants to do right by your clients, build your business, and change our world for the better.

But they are more than just eloquent descriptions of how fitness professionals approach program design…they are the 3 points of emphasis in program design. Like the points of a triangle – these archetypes are the fixed positions that function to keep trainers within the boundaries of the practice, while maintaining the freedom to explore within those very same boundaries.

As discussed earlier, a successful personal trainer exhibits traits of all three points. They are a hybrid of the archetypes. A simple perfectionist with an artist’s mind if you will. Most importantly, though, is that the most successful fitness professionals are those that can adjust their position within the triangle to meet their clients where they are (and better serve them on their journey to where they are going).

On any day, a trainer may need to keep it simple for a few clients, overthink and stress about a few others, and remain creative and loose for the rest. A great trainer realizes that one-size fits all only works with baseball hats and the airline seats found in coach. They know that they cannot lock themselves down into a single archetype and expect to help hundreds, if not thousands, of people make light weight feel heavy so that heavy weight feels light.

Success in this industry relies upon a fitness professional’s ability to learn, grow, and adapt just as they ask of their clients. With that in mind, what follows is the 6-step process to program design that has been used to guide thousands of clients towards results over the last decade. These 6 unique steppingstones integrate elements of the perfectionist, the simplifier, and the artist to deliver unparalleled experiences and results to paying clients.

The process that follows is specific and based upon objective data found in certifications, textbooks, and peer-reviewed journals. This satisfies the perfectionist. It is also straight-forward, linear, and thrives on preparation and established knowledge to optimize time management. This is a nod to the simplifier.

Lastly, but never least, the artist will find great appeal to the system because of its insistence on subjective, client-specific data in its later phases. Additionally, the variability and freedom of session-design serves to fulfill the innate desire to “make changes” as time passes.

DISCLAIMER

Obviously, like any linear system – the key is to embrace the entire process front-to-back to enjoy its benefit. A fitness professional cannot cherry pick the parts they like and discard the harder to work through bits and expect the same experience.

In this way, it is much like picking Maryland blue crabs during a summer hangout. For many, the claws are enough to satisfy their desire for protein and Old Bay – and don’t require the same investment of energy and time. Yet, without picking the actual crab itself and getting under the shell to find the dense meat – you’ll leave the table hungry and lament the meal and complain about orange seasoning being under your fingernails.

To the person who picks, and eats, the entire crab – it is a worthwhile experience full of food, flavor, and socialization. It is a journey meant to be experienced front-to-back. From setting the table with newspaper, making side dishes, filling the cooler with light beers, and ultimately picking for hours – there is no step that exists without the others.

So, as you go into the 6-step process below- embrace the journey.

STEP 0 – KNOW YOUR STUFF

It should go without saying, but we are going to highlight it anyway. If you want to be an excellent programmer that delivers Pain-Free results to all who trust you, then you need to invest in your education constantly. Your ability to be creative, to simplify, and to perfect a training program relies on a deeper understanding of the foundational sciences that drive our field as well as the many proven program design methods in the marketplace.

It isn’t enough to get a certification, train a few sessions, and occasionally read an article like this. That much is expected. Instead, you should seek counsel from more experienced peers, attend conferences and certifications like our PPSC workshops, and practice frequently.

There is a story of Kobe Bryant refusing to leave a workout for Team USA basketball until he made 800 shots; a practice that lasted almost seven hours. While you may not need a programming session to last one third of your day to be great in this industry, it does represent what you could give to be the best at your craft.

Be the student your clients hope you are!

STEP 1 – CHOOSE YOUR MICROCYCLE LENGTH AND PRIMARY TRAINING EFFECT

The first true step of the program design process is also the simplest.

First, we must outline the length of our microcycle, the smallest unit of a periodized training program. On average, a microcycle is a 4–8-week period dedicated to a specific training effect. This block of time allows for adaptation to occur within the body, whether it is musculoskeletal, neuromuscular, metabolic, or some combination of all the above.

Anything less than four weeks doesn’t provide enough stress over time to trigger adaptation. Meanwhile, any microcycle exceeding 8 weeks runs the risk of running stagnant and pushing a client towards psychological or physiological burnout.

Obviously, a client’s training history, current fitness level, as well as their commitment to proper nutrition and recovery practices will impact the length and efficacy of any microcycle. In fact, the next step is also based entirely upon our client’s goals, needs, and abilities.

Once we’ve established the length of our program, we must shift our focus to establishing its principal training effect. In short, a principal training effect is the primary adaptation we want to take place during a training cycle. Strength, power, hypertrophy, fat loss, aerobic capacity, muscular endurance, mobility, and general Pain-Free movement all constitute as such.

Contrary to the belief of our clients, and the practices of far too many trainers, the best programs do not try to accomplish too much at once. The conditions for any of the adaptations mentioned need to be right for us to maximize their benefit. A strength or hypertrophy program does not succeed if a lot of the training demands involve aerobic output or muscular endurance repetition ranges, and vice versa.

Instead, we want to outline a specific focus (and one secondary benefit) of our microcycle. In doing so, we can better structure every decision that follows. In this way, Step 1 establishes the parameters of our client’s training program – like bumpers on a bowling alley.

The result of Step 1 can look like the following examples:

8-Week Micro (Primary Emphasis = Hypertrophy / Secondary Benefit = Strength)

4-Week Micro (Primary Emphasis = Aerobic Capacity / Secondary Benefit = Fat Loss)

6-Week Micro (Primary Emphasis = Pain Free movement / Secondary Benefit = Mobility)

Remember, all training programs should be built to honor the unique goals, needs, and abilities of each client you work with. Our professional opinion informs our decision-making process, of course, but we should always honor our clients spoken goals.

STEP 2 – ESTABLISH WORKOUT FREQUENCY AND WEEKLY PERIODIZATION

Once we have established the general parameters of our training program it is time to become more specific to our client’s needs. First is noting how many training sessions will occur per week under your guidance (as well as without).

Training frequency is almost always dictated by a client’s availability. On average, a personal training client will work with a trainer twice per week. Some clients will engage in three or four and others will only pay for one session per week. The success of a training program depends on building according to a client’s ability to train with you.

Client frequency influences many factors of program design. The following 10 considerations are most impactful:

Movement Pattern Deployment

(What patterns are trained on what days?)

Movement Pattern Frequency

(Do we train a pattern multiple times per week/session?)

Movement Pattern Volume

(How much time do we invest in each pattern?)

Accessory Training Pattern Deployment

(How much time is left for other training efforts?)

Accessory Training Volume/Intensity

(How much time do we invest in the “small rocks”?)

Training Session Density

(How much work must fit into a single session?)

Training Session Frequency

(How often do we execute a particular session?)

Training Session Volume

(How much workload is experienced in each session?)

Off-Day Training Frequency/Demands

(How much is a client responsible for alone?)

Weekly Periodization

(How do we align the workouts to maximize benefit?)

The final consideration, weekly periodization, is an important step for personal trainers to consider. It is important to build an appropriate weekly schedule for clients that is periodized in a manner that allows for maximal training effect, appropriate recovery days, and enough flexibility to reflect the randomness that is human life.

A key definition, periodization refers to the session-by-session or week-by-week adaptations within a microcycle that allows for a client to experience a broader range of stimuli over the course of a program without overtraining or risking injury/fatigue/burnout. For the average client, weekly periodization might look like the following chart:

When looking at the methods of periodization for a microcycle (and the week-by-week progression within) we are best suited to use one of the following two options:

1. Linear Periodization

2. Undulating (Non-Linear) Periodization

*For the purposes of this section, all discussion of the periodization methods is assuming a client is training at a 3x/week interval.

If you are looking for more detail in Periodization options, check out this article by PPSC Instructor Dan Stephenson HERE

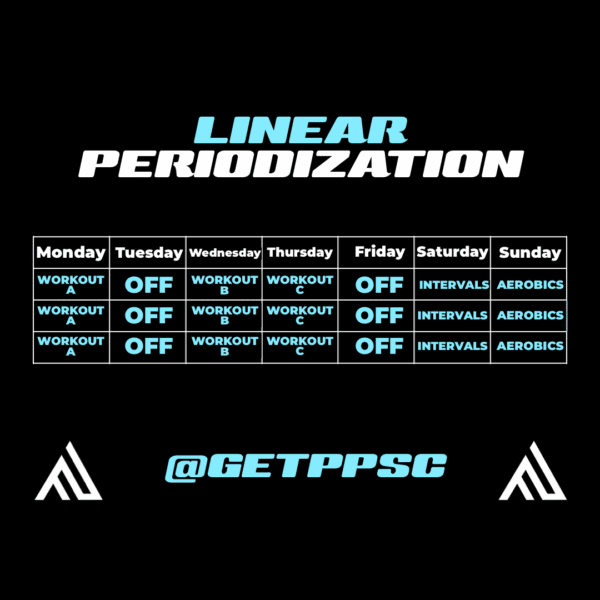

LINEAR PERIODIZATION

Every workout and weekly training schedule is kept constant throughout a given microcycle. In this style of programming, Workout A in Week 1 looks exactly like Workout A in Week 8, but with the impact of progressive overload driving the performance output upwards for a specific variable.

For example, a linear training program designed to improve muscular endurance would program increasing repetition demands week-by-week to move the client towards that outcome. A strength program might decrease repetitions but increase load week-over-week to improve neuromuscular output and cross-sectional area of muscle tissue. There are changes in workload over time, but the program remains mostly constant.

Linear is almost always the best program design method (if not the only) that works for once-per week clients.

The figure below best demonstrates linear programming in an imaginary 3-week training block:

UNDULATING PERIODIZATION

Also known as non-linear periodization, this method seeks to rotate training effects, or their place within a weekly schedule, or some combination of the two in a way that optimizes physiological adaptation principles while promoting psychological enjoyment. There are 3 predominant ways that you can utilize undulating periodization:

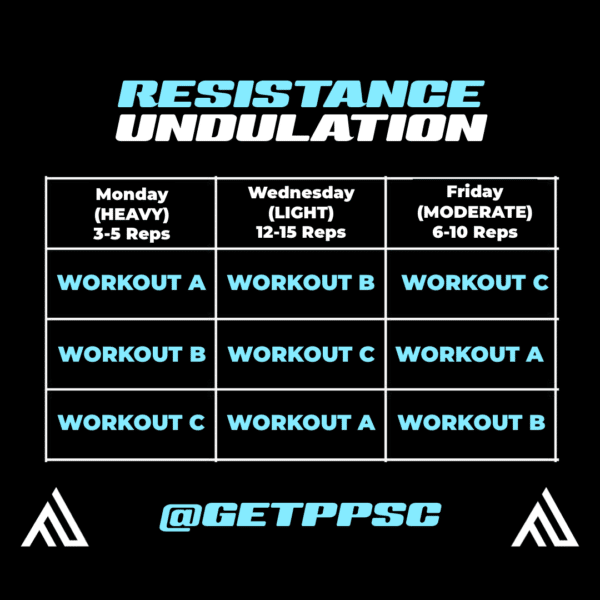

1. Resistance Undulation – Assigning a day of the week a load value and undulating the program days through them.

For example, Monday is assigned “HEAVY (3-5 reps)” for the entirety of a 6-week microcycle. A client who trains 3 days per week will see Workout A, Workout B, and Workout C be cycled through on Monday (as well as their other training days) – thus providing at least 2 HEAVY resistance days for each workout design. The chart below highlights further:

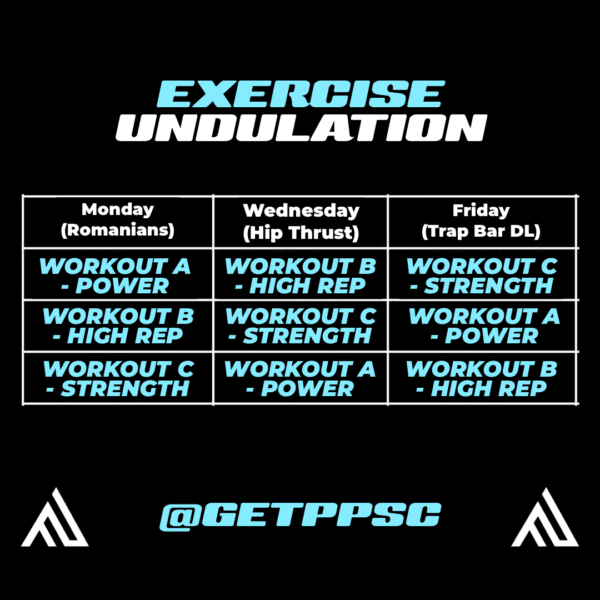

2. Exercise Undulation – Emphasizing a specific training pattern during a microcycle (like the hinge) by assigning a primary exercise to a given day of the week and undulating the way that exercise is performed week-by-week.

For example, Romanian Deadlifts are performed on Monday, Hip Thrusts on Wednesday, and Trap Bar Deadlifts on Friday. Workout A is power emphasis, Workout B is high repetition emphasis, while Workout C is peak strength. There are 3 primary hinge efforts in each training week – but the program rotates how those exercises are trained week by week. The chart below visualizes this:

3. General Undulation – Rotating the workouts week-by-week to change the pace and vary the training stimuli.

The simplest variation does not consider anything other than rotating the program days week-by-week to provide adequate rest to challenged muscles and variety to the client’s mind. The workouts cycle like the charts above, but with no special demands regarding resistances, exercise selection, or other variables.

Workout A will remain the same week-by-week even if it occurs on the same day, and so on.

DEVELOPING A PERIODIZATION STRATEGY

Arriving at the best strategy for your client does not need to be as stressful as trying to launch a rocket to space (or guide it back for landing). The right method of periodization will be decided by looking at the following:

A client’s weekly training frequency (More Days = More Choices)

A client’s skill level with training, recovery, and nutrition (More Skill = Higher Demands)

A client’s capacity to exercise on their own (What can they honestly do for themselves)

A client’s training goals and needs (What method makes sense for their goals?)

Lastly, always build in a bit of flexibility during this phase of program design. You’ll want to have contingency plans in place for the times when life gets in the way and a client misses a workout, or when your client can/needs to change the intensity of their day’s session to reflect their current stress.

The following 3 tips are always useful:

Build Workout “AZ” – the catch-all workout that loosely summarizes the training effects and focuses of the normal programmed training sessions. It is perfect for the weeks when a client travels, falls ill, or requires a break from their normal routine.

Build “Go” and “Slow” – versions of your normal training programs. Sometimes clients don’t feel well, are tired, or need a break. Other times they are feeling great and are ready to push their workouts. For these times, build in the potential to adjust intensity up or down by 5-10% at a moments notice.

Program in Pencil – Nothing is set in stone. From this phase forward, you’ll want to retain the ability to adjust your course as life, goals, and training capacity change. Writing in pencil is not a sign of weakness – it is the truest sign of confidence.

Once we have settled upon a weekly structure and the general flow of the program, then it is time to build individual workouts.

STEP 3 – SELECT YOUR PRIMARY AND SECONDARY MOVEMENT PATTERNS

During this phase we want to establish the “big rocks” of the training program. In translation, the big rocks are the major movement patterns that are proven to deliver results and will require the greatest effort by our client.

You know these patterns; squat, hinge, lunge, push, pull, carry and rotation, the fundamental training efforts. To be clear, this is not exercise-specific selection. Instead, the third phase of program design emphasizes placing the patterns appropriately throughout the week to promote performance and recovery equally. Each training session should have primary and secondary efforts.

Primary Training Effort – The biggest opportunity to progress a client or the biggest focus of a training block. The exercise in this slot is the MOST important of the entire program. Always programmed in the 1-A slot. Always a foundational movement pattern.

Secondary Training Efforts – Important, yet malleable training efforts that can contribute greatly to the progress a client experience. Secondary training efforts are always foundational movement patterns that either support the primary training effort with additional workload, or function to train the body’s other patterns. Typically found in the 1-B, 2-A, 3-A slots of a training program.

Complimentary Efforts – Training efforts that are designed to impact the same muscles, movements, or performance aspects of the PRIMARY training effort. Common for strength and hypertrophy workouts.

Non-Competitive Efforts – Training efforts that do not use the same muscles, movements, or planes of motion as the PRIMARY training effort. Common for metabolic workouts.

For each workout there should be (1) Primary Training Effort and no more than (2-3) Secondary Training Efforts. How you align these patterns will be based upon your client’s goals, needs and abilities. Furthermore, the frequency of training will dictate exactly how many patterns need to be trained during a session.

Lastly, a client’s ability and experience will dictate which patterns are trained heavy, which could be made plyometric, and which should emphasize form and function first.

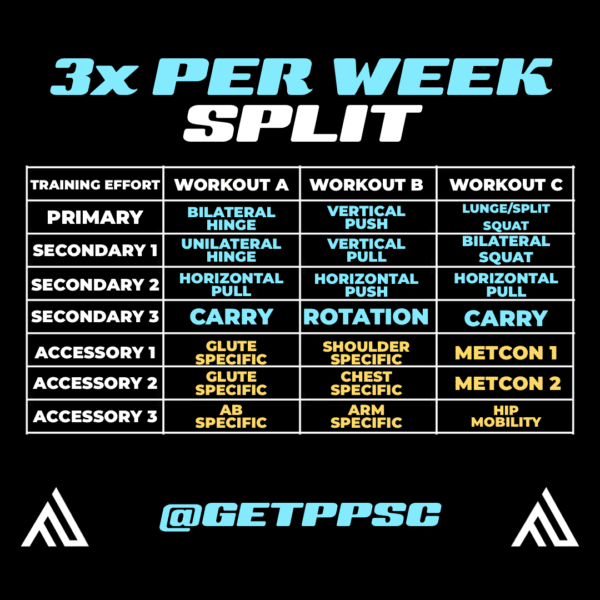

The chart below highlights how this might look for a client who trains 3 times per week:

The completion of Step 3 illustrates a transition from the big picture to the finer details. If a program design process stopped here there would be enough information to construct a challenging, periodized program that targets that foundational movement patterns even if it lacked clarity and detail.

Obviously, more detail provides greater opportunity for results and that is where steps 4-6 are critical.

STEP 4 – SELECT YOUR ACCESSORY TRAINING PATTERNS

While training the big rocks will lead to MOST results clients and trainers seek from a program – there is always room for accessory efforts that improve muscles that clients want to see, improve performance in the foundational training efforts, or provide the “feeling” that many clients pay for. These patterns, known as accessories, are critical for client “Buy-in” – the process in which a client trusts, absolutely, that this program is the right one for them.

There are 4 distinct types of Accessory Efforts:

1. MUSCLE BUILDING/TONING

Yes, toning isn’t a real thing, but to many clients it is a word they use to describe seeing their muscles through their skin without looking like the Doppelganger of an IFBB pro. Whether a client wants to build/define their glutes, arms, shoulders, or calves – some accessory training patterns are added into the program to satisfy their desire to look better naked (and that’s OK).

2. PERFORMANCE ENHANCEMENT

Some accessory training patterns still relate to the primary training efforts. Adding loaded hip mobilizers in between sets of single leg deadlifts might be the right overload stimulus to enhance your client’s sumo deadlift totals. Or adding more sets of the Rusin’ 3-Way-Shoulder Warmup series at the end of the workout is going to keep building their bench or pushups.

3. CORE

Nearly all clients could use more direct core training efforts, especially those that demand stability of the spine in all three planes of motion. This pattern, known as the CARRY pattern is one of the 6 foundational movement patterns in the PPSC, but it is often trained towards the end of a workout, thus making it a hybrid accessory. Furthermore, direct abdominal training such spinal flexion, extension, and rotation can be programmed as an accessory too.

4. METABOLIC AND SWEATY

Some clients need to burn more calories and improve their anaerobic metabolic capacity. Others just want that feeling of being out of breath and sweaty at the end of a session to confirm that their money was well spent. Regardless of the motivator – those rope slams, medicine ball chops, and plyometric lunges can be programmed here.

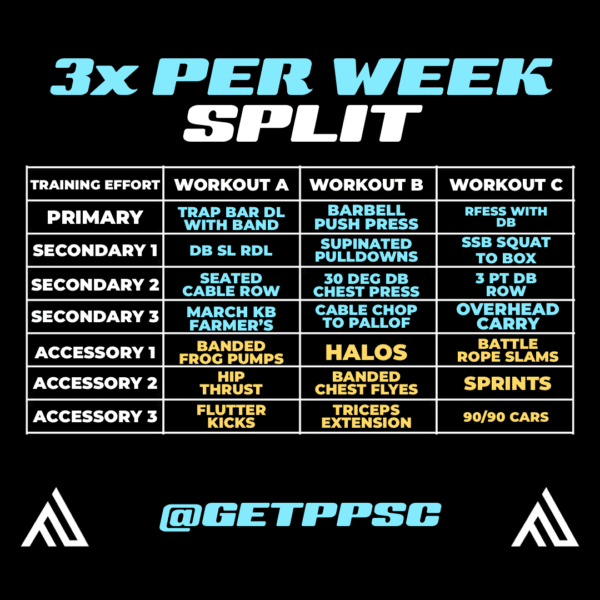

The chart below provides accessory efforts to the primary and secondary patterns from step 3:

Once you have selected your accessory patterns, then it is time to begin painting in the numbers. The picture is drawn, the desired outcome is clear – now we must provide the color that brings a training program to life. The workout design includes the exercises we choose and the intensity variables we employ.

STEP 5 – CHOOSE CLIENT-SPECIFIC EXERCISES

At this phase most of the work is done. Your client’s program is outlined in a way that clearly lists what patterns will be trained on what days and where in each Workout design they belong.

Now all that is left is the choosing of the specific exercise that is most likely to cause positive adaptation in their body while minimizing their risk of injury or overtraining. As we teach in our course, there are hundreds of exercises that can be used to move a client from the proverbial point A to point B – it is our job as the professional to choose the right one.

For example, many trainers who want to get their clients to squat heavier will immediately utilize barbell back squats, or front squats to elicit maximize stress. Yet, their client might have been better served to build requisite core strength from goblet squats, adductor and glute strength from lateral split squats, and depth from Spanish squats…

Our goal in this phase is to bring the specific exercises to the program that will get the results, safely, for our clients. Below is a visual to show the progression through Step 5:

STEP 6 – CHOOSE CLIENT AND GOAL SPECIFIC DEMAND RANGES

The final step of a training program design process is the one that is the least specific. There are not any studies that say you need exactly 5 repetitions, or specifically 4 sets, to improve an exercise or get results.

Moreover, most clients need a little flexibility session-to-session to deal with their stress levels while also promoting a “winning” mindset at the end of every hour.

For this reason, the final step of your program design process doesn’t demand specific sets, reps, loads, or rest periods to be assigned. Instead, it emphasizes providing the logical range of each demand as client ability, session-time, and equipment availability may allow. This step is the best example of programming in pencil.

To be clear, there are plenty of program design models that do ask for specific outputs. The cube method, 5-3-1, 5×5, 8×3, and German Volume Training all require specific load percentages, sets, reps, and rest periods be observed in their protocols. Approaching any program in this manner is fine so long as you are certain your client can deeply commit to such a strict protocol.

As is the experience of many personal trainers, a client’s availability and willpower can fluctuate, which makes a more generalized “range-based” Step 6 ideal for many. Furthermore, programming in this way provides your client space to excel and the freedom to fail, two psychological experiences that are critical to the success of a long-term training relationship.

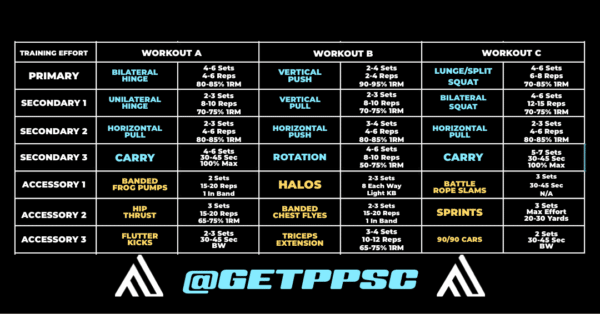

The chart below demonstrates what Step 6 looks like in visual form and provides context to this section.

ON WARM UPS

Getting clients ready to perform is critical to the success of any training program. Even the best program can fail, or cause injury, if the client is allowed to go from “hello” to their first set without a scientific approach to physical preparation.

For those cases, the proven 6-phase dynamic warmup that is taught at all PPSC courses is critical to the success of a training session, and thus, a program. From self-myofascial release to central nervous system stimulation – it is critical for a client to optimize themselves before engaging in the challenging demands of training.

You can learn more about the PPSC approach to warmups here and here.

ON COOLDOWNS

Similarly, cooldowns are an often underrated and underappreciated part of the workout design. Far too many gym goers finish off their last sets, , gather all their jackets, move towards the exits – without or without their friends (Semisonic anyone?)

For starters, this is not the best practice for the cardiovascular system. The heart does not like not being given an opportunity to slow down and reregulate after a challenging effort, especially if it goes from high output to rest. No, the walk from the curl rack to your car door isn’t enough transition. Neither is your flex session in the mirrors of the locker room.

Instead, 3-5 minutes of dedicated mobility of the joints that had been trained in the session and 2-3 minutes of deep parasympathetic breathing is best. You can utilize the foam roller, stretching, and joint mobilization techniques to reduce tension, induce rest, and ease the body out of the stressed state.

Then, supine deep breathing with an emphasis on full diaphragmatic expansion is ideal for bringing down the nervous system, the cardiovascular system, and promoting early recovery efforts within the body.

The cooldown, like the warmup, is a critical part of the program design puzzle.

BUT IT’S ALL JUST ONE PIECE OF THE PUZZLE….

The success of a training program relies upon more than just the X’s and O’s of your training program. You could periodize perfectly, choose the right exercises, and coach your heart out…

And yet a client might still underperform, feel a muscle pull, or never quite buy-in to a given session.

Realize that all great plans are destined to fail just as often as they are destined to succeed. Life has a hilarious way of humbling the intellect and planner with random events, unforeseen twists, and frustrating adjustments to timelines.

This is why we program in pencil and honor our client’s needs, goals and abilities above all else. The system is important. The system works. But none of it matters if we become programming robots incapable of human connection, authentic empathy, and a true desire to make a session work.

No matter who you are as a programmer right now (perfectionist, simplifier, artist) – you can merge all approaches, apply a 6-Step system, and elevate yourself into an entirely new stratosphere. Our industry needs you.

Your clients need you.

The perfect program is simple, full of flare, and yet grounded in science and proof. It’s concrete, yet fluid…structured, yet flexible. It acknowledges that shit happens and that your clients love ice cream a little bit more than they love reverse lunges. It honors the science of physiological adaptations while understanding that Tuesdays tend to be stressful days or that Fridays always seem to be canceled in favor of Happy Hour.

The perfect program is built following proven steps that systemize and simplify the process for you, the trainer. It also provides freedom intra-session to the client to excel or dial back. It follows logic and reason but leaves room for empathy.

Write that program, every time!