No matter if you are beginner or a veteran to training, having some type of structure to your training regimen will provide you with better results than to have no structure at all.

Whether it be intentional or not, you have likely utilized some form of structure or progression in your training plan. The strategic manipulation of training variables such as sets, reps, load, rest periods, exercise selection, etc., within a training plan to elicit a desired response from training can be defined as periodization.

If you are looking to make any specific changes long term in the gym, some type of model approach is going to make a big difference. While the most people who walk in the gym workout “whatever they are feeling” that day, the ones who make the lasting results are the ones who have some type of structure around their fitness routine.

Lets discuss that structure and how it can come in varying levels of complexity.

PERIODIZATION

Periodization can be viewed at a macroscopic level all the way to a microscopic level and everything in between. When periodization is discussed, the organizational terms related to periodization are as follows:

Macrocycle – Typically thought of as the annual plan but depending on the training style and sport, can also refer to a timeframe of 6 months to 4 years.

Mesocycle – Most commonly viewed as the current training “phase” and refers to a timeframe of 4-8 weeks depending on the training style.

Microcycle – The intricacies relating to the individual training day up to 2 weeks.

As you can see, there is variance between the timeframe within each of these terms relating to the training style, sport, and individual athlete and coach. Additionally, there are various models of periodization and different theories and opinions on what approach is best.

To decide which periodization model is best suited for you, we must first define what makes a training plan successful, then examine the most common models and their unique characteristics, and decide which model is best suited to the needs of the individual.

CHOOSING A PLAN

There are several different nuances and theories that play into how a training plan is designed and to what periodization model is used. Don’t get too overwhelmed just yet. Most of the variations are subtle between these methods so you may be using one of the below already or unknowingly applying principles with high complexity. That is a good thing!

When it all boils down, there are three primary principles of training that must be respected for a training plan to successful.

SAID PRINCIPLE

The SAID Principle, an acronym for Specific Adaptations to Imposed Demands, refers to when the body is placed under some form of stress, it begins to make adaptations that will allow the body to improve at withstanding that specific form of stress in the future.

Regarding training stressors placed on the body, they need to be specific to the desired adaptation we are after. This includes everything down to the movements trained, loading used, velocity of movements, joint angles trained, skills developed, etc. The body will get better at what we practice.

PROGRESSIVE OVERLOAD PRINCIPLE

The Progressive Overload Principle states that to continue to make progress, the body must be forced to adapt to a stress that is greater than it has previously experienced. To put simply, we must do more over time to force adaptation.

The body will adapt to stress higher than the normal stimulus because it damages the system to a small extent. From small trauma to the muscle fibers all the way to overload of cognitive stimulus, we pushed the system further than it was prepared to go. The body – in its incredible nature – recognizes that elevated stress and prepares the body to adapt so that similar stimulus doesn’t affect the body in the same way.

The body is pushed beyond its limit over and over to create the stimulus of Progressive Overload.

GAS PRINCIPLE

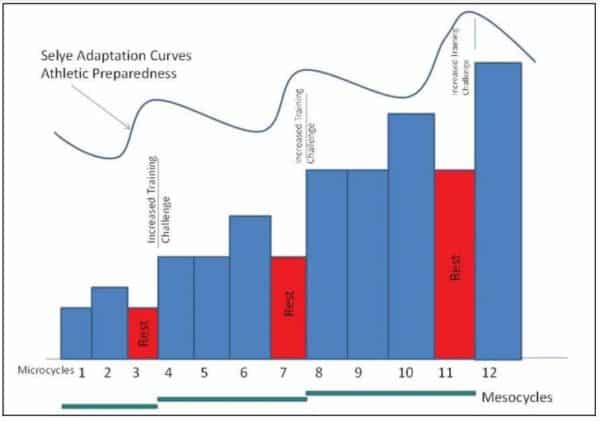

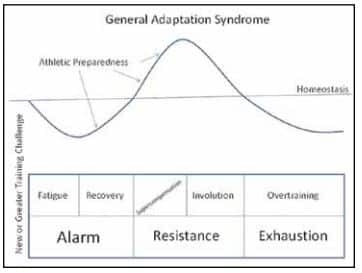

Coined by a Canadian endocrinologist, Hans Selye, the General Adaptation Syndrome (GAS) Principle states that the body undergoes three phases when experiencing a new stimulus:

ALARM PHASE: Initial shock of new stimulus. An example would be the fatigue and soreness felt after performing a new exercise

RESISTANCE PHASE: The adaptation of the new stimulus. This is where the body begins to bounce back and regain a sense of normal.

EXHAUSTION PHASE: The fatigue phase, if we remain in this stage for too long in training we are dipping into overreaching and then overtraining.

To put simply, training needs to allow for recovery and adaptation to avoid overtraining and maladaptation.

The training plan that honors these three principles the closest AND fits well with the individual’s needs accurately will be the best option.

Now that we have established what makes a training program successful, let us explore the most common periodization models and what makes them unique in their approach.

LINEAR VS. NON-LINEAR

Although there are an infinite number of programs out there, there are some commonalities and overarching themes that most every program follows. When we break it down to the most fundamental components of periodization, there are TWO primary designs of periodization, consecutive and concurrent.

Within the consecutive design, the overarching theme is the sequential development of fitness qualities over time. The concurrent design differs in the approach with the simultaneous development of multiple fitness qualities over time.

Within these two primary designs, we can break these down further into the organization within each design. The two most common models within the consecutive design are linear periodization and block periodization.

The two most common models that are concurrent in nature are undulating periodization and conjugate periodization.

LINEAR PERIODIZATION

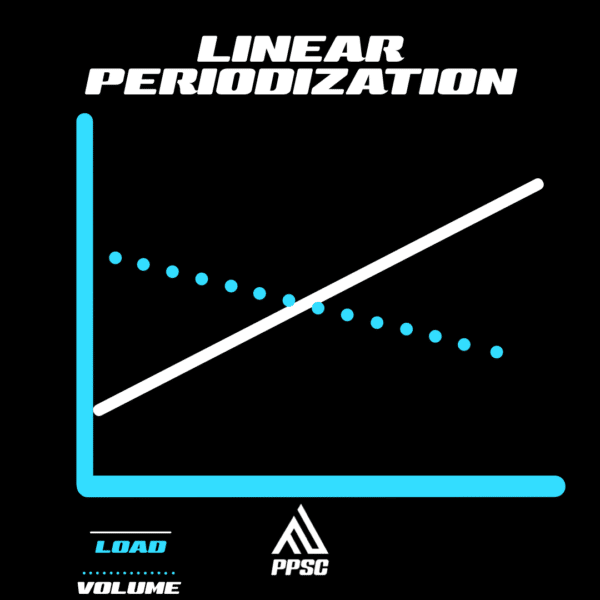

Linear periodization, often called traditional or western periodization, can be characterized by a training plan that consists of a steady progression of intensity on a limited number of exercises with a steady reduction of training volume over time.

This model works well for beginners as the loads used in the beginning of a program are lighter and the exercises are not rotated on a regular basis allowing for long term skill development. This can be a double-edge sword for our advanced trainee, as they may run the risk of overuse issues with the stagnation of exercise variety.

Linear periodization can also be utilized in the short term for peaking for a competition.

One of the potential pitfalls of the linear periodization model for strength training is that it operates on the assumption that the volume will directly translate into intensity as the program progresses.

Although the movements are practiced with repetition throughout the program, remembering the SAID principle, the act of lifting heavy is also a specific skill. The longer the program, the longer time spent away from the specific stimulus of lifting heavy in the beginning of the plan and the skill may not transfer as well as intended for an intermediate or advanced trainee.

Another potential downside of this model is the initial fitness qualities developed in the beginning of the program will potentially decay by the end of the program. With the focus initially being on volume, the qualities developed through training with higher volume may decay during the gradual switch to focusing on intensity.

BLOCK PERIODIZATION

Block periodization operates in a similar manner to linear periodization although training is organized in to specialized blocks (think mesocycles) designed to develop specific fitness qualities. The sequence of these training blocks is intended to build upon the previous block leading into a natural peak.

Within these training blocks, there are less “rules” as it comes to volume and intensity when compared to linear. During an accumulation block for example, we may see an increase in volume and intensity in the short term. Exercises will generally remain throughout each block and may or may not be continued in the consecutive blocks.

The flexibility of block periodization allows it to be effective for most trainees if the program is respecting the exercise principles discussed earlier and addressing the individual’s needs. The potential downside to block periodization is, like linear periodization, the potential decay of fitness qualities over the duration of the program.

The simplicity of the consecutive model having a limited exercise selection and time to develop the motor patterns within these exercises fits well with beginners. These programs tend to look much more organized on paper and lend themselves naturally to a peak.

This can work well for athletes that are interested in peaking on a specific date. This model would not as compatible well with athletes with longer sport seasons or have no reason to peak such as tactical athletes. For these athletes, the concurrent model may be better suited.

UNDULATING PERIODIZATION

Undulating periodization is characterized by the effort to increase multiple training qualities simultaneously through a regular rotation of training stimuli. The rotation of efforts typically can occur on a daily, weekly, or even bi-weekly basis.

For example, in a daily undulating program, one day of the week may focus on hypertrophy, while the next session is focused on developing power, and the following on strength.

The frequent rotation and concurrent attempt to increase and/or maintain multiple training qualities lends itself to be more suited for an intermediate to advanced trainee that has built up a solid training base already to build upon and is likely not consistent enough for a beginner trainee to develop a solid base.

CONJUGATE PERIODIZATION

Conjugate periodization is a cousin to undulating periodization in its design with the primary difference being that conjugate programs are characterized by their frequent exercise rotation and the regular implementation of the maximum effort method.

The maximal effort method involves building up to a top set of a heavy single rep on an exercise that is typically rotated weekly.

Like the undulating model, conjugate periodization is best suited for an advanced trainee that has a solid training base and enough knowledge to identify which exercises will be most appropriate for their goals without neglecting potential weaknesses in training.

The potential downsides to conjugate are that it can be too complex for a beginner and potentially detrimental to performance with an intermediate or advanced trainee if the program is not designed well for them. Additionally, the constant rotation of exercises may limit the skill acquisition of some trainees.

With proper implementation and programming, conjugate periodization can be remarkably effective and does a good job at avoiding overuse issues with the wide variety of exercise selection.

The concurrent models do not have a natural peaking phase and can serve as a good periodization style for athletes with longer seasons.

Although the various fitness qualities trained may or may not be optimally developed with the split efforts amongst qualities, the concurrent model does do well with maintaining and/or slightly improving various qualities.

This can be useful for in-season training athletes with longer seasons or tactical populations in which peaking is not a concern.

CONCLUSION

As you can see, each periodization model has its strengths and potential drawbacks depending on the individual’s needs, goals, training experience, and even preference. If the individual is addressed within the program, and the program abides by the training principles in respect to the goals, any periodization style can be effective.

Truthfully, many programs do not live entirely within one model or another. Some of the most effective coaches I know are masters of blending elements from each periodization style to get the most out of their clients. The beauty of program design is it is both an art and a science and the best methods are always evolving.