Perhaps no exercise rose to infamy more quickly than barbell good mornings when, in 1969, Bruce Lee reportedly blew out his back while performing them. He had to take a layoff from training for a long period of time thereafter, and while he did get back to training (to no one’s surprise), it was said that he battled back pain for the rest of his life.

Bruce Lee aside, there’s an ongoing debate amongst fitness professionals as to where or not the barbell good morning is a “bad” exercise. However, one point that virtually everyone can agree on is that some exercises – not just barbell good mornings – are unequivocally better than others from a risk vs. reward standpoint. For example, while both trap bar deadlifts and barbell deadlifts are safe and effective when done right, there’s no denying that the former is a lot easier to perform well – and far less likely to be butchered – than the latter.

Why does risk vs. reward matter? For fitness professionals and gym-goers, weighing risk vs. reward should be one of the primary drivers – if not the primary driver – of exercise selection. If there’s a significant risk to performing an exercise, the most sensible approach is to ditch it in favor of a safer alternative. It sounds like common sense, sure, but common sense isn’t always so common.

Going back to barbell good mornings, there’s one camp – namely, powerlifters and Westside Barbell devotees – who swear by their ability to strengthen their squat and deadlift numbers while reducing injury risk under load. Conversely, there are others who avoid barbell good mornings at all costs; after all, if Bruce Lee – the Dragon himself – can get hurt during barbell good mornings, who’s to say that anyone else is immune?

The question then becomes, what’s the deal with barbell good mornings? Are they safe, or are they dangerous? Are they effective, or are they worthless? Most importantly, should you and/or your clients perform them?

As is the case with any other exercise selection question, the answer boils down to risk vs. reward.

THE GOOD: THE PURPORTED BENEFITS

For those who aren’t familiar with them, barbell good mornings are a posteriorly loaded, top-down hinge movement. They’re almost identical to Romanian deadlifts (RDLs) in terms of the muscle actions and muscle groups involved, with the only difference – albeit a big one – being that the bar placement on the upper back changes the position of the load the subsequent lever profile.

Like any other hinge movement, barbell good mornings train the posterior chain – namely, the glutes and hamstrings – via hip extension. As such, they provide a loaded stretch throughout the backside, strengthen the spinal erectors – whose basic job is to maintain structural integrity under load – and challenge the upper back and scapular stabilizers to work to keep the bar in place.

Above all else, however, the most common reason for implementing barbell good mornings comes down to their “sport-specific” benefits to powerlifting. For the squat, they’re used to train strength out of the hole in the midst of technique-gone-wrong situations. As such, they’re meant to aid lifters who have a tendency to shoot their hips up on the initial ascent – which is common under maximal loads – by helping them build reversal strength on the eccentric-to-concentric transition. As for the deadlift, barbell good mornings are used to reinforce full-body tension and “big air,” train anti-flexion with a full loading of the posterior chain, and place a focus on lower back strength and upper back stability (i.e., not rounding at the upper back).

Perhaps most importantly for powerlifters, barbell good mornings are often used to develop strength and stability in otherwise “disadvantageous” positions – under maximal loads, no less – which is said to make them useful for reducing injury risk if/when technical breakdown occurs.

THE BAD AND THE UGLY: THE RISKS

Above all else, the primary risk of barbell good mornings stems from the fact that they can impose a boatload of shear force onto the spine, which is basically defined as force applied parallel to the surface (or close to it). Since shear force magnitude is one of the strongest predictors of both acute injury risk as well as chronic low back pain, it’s not something to be taken lightly (1).

Per Dr. Stuart McGill, there are two types of shear force. The first is reaction shear, which occurs as a result of gravity pulling the load and the upper body towards parallel. The second is joint shear, which is the sum of reaction shear and muscle/ligament shear, or how much load the passive structures (e.g., discs, ligaments, fascia) have to take on.

As to how barbell good mornings impose shear force, the biggest issue is that it’s tough to avoid rounding at the lumbar spine at the bottom of the movement. While lumbar flexion isn’t bad in and of itself, the story is entirely different if/when rounding occurs with a posterior load at end-range flexion. As both elements are present, the otherwise protective musculature of the low back becomes “silent” and loses its ability to contribute – a phenomenon known as “flexion-relaxation” – which shifts the brunt of the load onto the passive structures, in which case things can get ugly pretty quickly (2).

Moreover, end-range lumbar flexion – in comparison to lumbar flexion elsewhere – is also the point at which there’s a three-fold increase in shear force as well as a simultaneous decrease in shear tolerance (3,4). Add to the fact that reaction shear is at its greatest when the upper body is parallel to the load (as it occurs during barbell good mornings) and the result is a perfect storm of spinal stress.

To make the waters even murkier, insufficient upper body mobility and/or a lack of scapular stability can cause the bar to roll forward onto the neck, which not only increases shear force but also puts the shoulders into a potentially troublesome position of extreme external rotation and abduction.

WEIGHING RISK VS. REWARD: ARE BARBELL GOOD MORNINGS WORTH IT?

All in all, the list of risks that accompany barbell good mornings sound eerily similar to the disclaimers at the end of a prescription medicine commercial. Does that mean that they’re a bad exercise? Not necessarily. Does that mean that they’re a bad exercise for non-powerlifters? Probably.

To steal a hypothetical example from Eric Cressey, say that there are 100 gym-goers. Right off the bat, about two-thirds of the group – say, 65 people – are likely too deconditioned to perform heavily loaded barbell movements, let alone good mornings. Of the remaining 35, 20 are probably better off focusing on alternative hinge-based exercises to strengthen their posterior chain with less risk, while another 3 may have to stay away due to previous back issues. Of the 12 individuals left, 8 might find that their technique breaks down when they go heavy, in which case they should stick to light-to-moderate loads. The final 4? Have at it!

The point is that, for almost all individuals who aren’t powerlifters, barbell good mornings are probably a bad idea. Taking the risk vs. reward concept into account, there are simply too many equally effective – if not more effective – alternatives that are safer and easier to perform well (as detailed below). Why not opt for those? As the old cliché goes, there are many paths that lead to Rome. Likewise, there are many paths – namely, many alternative hinge movements – that can produce the same training effects as barbell good mornings with significantly less risk.

Does that mean that they’re a bad exercise for powerlifters? Not necessarily. In many cases, barbell good mornings can have unparalleled “sport-specific” benefits. Due to their posterior loading, they not only have a direct carryover to squats (and deadlifts, albeit less directly), but also target low back/anti-flexion strength and stability in otherwise vulnerable positions, and thus mitigate injury risk under a maximally loaded bar.

Still, the caveat is that powerlifters should take an honest look in the mirror and assess whether or not they can perform them with technical mastery while maintaining full-body tension, spinal neutrality, and a strong brace. Even then, hoisting up big weights during barbell good mornings comes with the price of higher axial loading, which may hinder recoverability and rob training capacity for future training sessions. As such, while barbell good mornings have merit for powerlifters, they should still be programmed strategically and performed with an emphasis on pristine technique.

ALTERNATIVES TO BARBELL GOOD MORNINGS

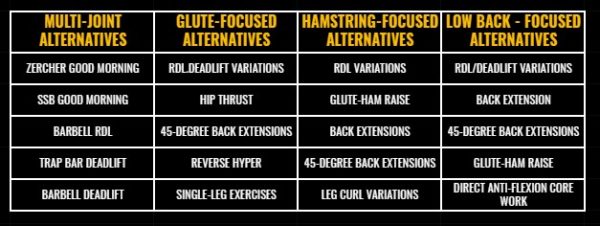

Like any other exercise – excluding the big three lifts for powerlifters – barbell good mornings are far from mandatory. Above all else, selecting exercises should be done by prioritizing movement patterns first, and then plugging and playing thereafter based on individual goals, needs, training/injury histories, etc. If barbell good mornings are the wrong choice for you and/or your clients, the following options are safe and effective alternatives.

MULTI-JOINT ALTERNATIVES

For those who like pushing big weights on multi-joint movements, there are several suitable alternatives that can deliver all of the same results with less risk.

ZERCHER GOOD MORNING

The most direct alternative is the zercher good morning performed with a barbell or dumbbell(s), as it provides all of the same benefits as back-loaded good mornings with a couple of additional perks. On top of working the posterior chain all the same, using an anterior load creates a counterbalance that makes it easier to push the hips back more authentically. At the same time, they facilitate full-body tension almost by default, as there’s a huge need to create a 360-degree brace to prevent the bar from falling forward. Plus, the anteriorly loaded position provides immediate proprioceptive feedback and heightened body awareness, which can aid in reinforcing spinal neutrality.

ROMANIAN DEADLIFT (RDL)

The second alternative is the RDL, which can be performed with a barbell or trap bar to allow for heavier loads, or with dumbbells/kettlebells to scale up the reps with ease. The beauty of RDLs is that they’re almost identical to barbell good mornings from a mechanical standpoint – as they employ similar degrees of hip flexion/extension as well as knee flexion – albeit with an anterior load that reduces shear force and mitigates the risk of buckling under a bar. From a muscular standpoint, RDLs show a bit more hamstring activity and a slight decrease in glute activity compared to barbell good mornings, although the heavier loads that they allow for may outweigh the slight trade-off in glute recruitment.

Check out this article for the 30 BEST RDL variations

GLUTE-FOCUSED ALTERNATIVES

For targeting the glutes more directly, there are several exercises that can produce similar or more pronounced training effects than barbell good mornings with significantly less risk. Hip thrusts, for one, are a more biomechanically efficient exercise in that they strengthen the glutes at the end-range of hip extension – unlike barbell good mornings, which involve less hip extensor activity near lockout – while allowing for heavier loads and minimal axial loading.

Back extensions and reverse hypers are additional options that can, in the same manner, hammer the glutes while sparing the spine. Albeit a much different motion, single-leg exercises like Bulgarian/rear-foot elevated splits squats, reverse lunges, 1-leg squats, and step-ups can hammer the glutes just as hard or harder than barbell good mornings with minimal risk and virtually zero axial loading.

HAMSTRING FOCUSED ALTERNATIVES

Aside from RDLs, back extensions and 45-degree back extensions have been shown hit the hamstrings harder than barbell good mornings with a similar order of contractions (glutes, hamstrings, erectors). Other options that target the hamstrings more directly like glute-ham raises and leg curl variations (e.g., machine, stability ball, slideboard) have been shown to elicit moderately higher levels of proximal hamstring activity and far more activity in the distal regions.

LOW-BACK FOCUSED ALTERNATIVES

Low back strength can be targeted in a myriad of ways, most notably via similar hinge exercises that allow for heavy loading (e.g., front-loaded good mornings, RDLs, barbell/trap bar deadlifts). By the same token, some studies have suggested that glute-ham raises may hit the erectors even harder than barbell good mornings (5). Other options that can train low back strength with minimal stress include reverse hypers, back extensions, and more “direct” exercises like back extension iso-holds.

CONCLUSION

Powerlifter or not, there’s no denying that the risk-to-reward ratio of barbell good mornings is hardly favorable. While they may have merit for powerlifting purposes – especially for serious powerlifters, like the monsters at Westside Barbell – that’s not to say that they should be stuck into programs dogmatically and without reason. For everyone else who doesn’t compete in powerlifting, barbell good mornings probably aren’t worth it. Quite frankly, there’s a wide array of alternatives that are just as effective – and in many cases, more effective – than barbell good mornings with exponentially less risk. No exercise is mandatory, and barbell good mornings are no exception.

REFERENCES

1. Norman, R. et al. “A comparison of peak vs cumulative physical work exposure risk factors for the reporting of low back pain in the automotive industry.” Clinical biomechanics (Bristol, Avon) vol. 13,8 (1998): 561-573.

2. Descarreaux, M., Lafond, D., Jeffrey-Gauthier, R., Centomo, H., & Cantin, V. (2008). Changes in the flexion relaxation response induced by lumbar muscle fatigue. BMC musculoskeletal disorders, 9, 10.

3. Yingling, V. R.. “Shear loading of the lumbar spine, modulators of motion segment tolerance and the resulting injuries.” (1997).

4. Potvin, J R et al. “Trunk muscle and lumbar ligament contributions to dynamic lifts with varying degrees of trunk flexion.” Spine vol. 16,9 (1991): 1099-107.

5. McAllister, Matt J et al. “Muscle activation during various hamstring exercises.” Journal of strength and conditioning research vol. 28,6 (2014): 1573-80.