The function of a joint in the human body is dictated by its anatomical design. Bones come together to form joints and muscles actively pull on these bones in a direction allowed by a joint and the tendons/ligaments within, thus forming a joint “degrees of freedom”.

Stable hinge joints, such as the knee and elbow, provide tremendous force production while sacrificing mobility, or degrees of freedom. Their simple design inhibits movement in the frontal and transverse plane but allows for efficient flexion and extension. We are not seeking enhanced mobility in these joints.

But then there is the hip, a mobile joint by design, but capable of producing a high level of force in life, sport, and training. The hip joint, with access to all 3 degrees of freedom, is designed to handle high velocity and high-tension stimuli through and in all positions.

The incredible capacity for both mobility and force production makes the hip joint arguably the most important area of emphasis for fitness professionals and dedicated trainees. A complex region such as the hip requires a more complex training program that factors in nuance and specificity while utilizing the foundational patterns to their fullest potential.

Training the hip appropriately requires an understanding of hip anatomy and physiology, the positional relationships with neighboring joint segments, and the effect of irradiation and the synergistic spiral effect on the stability and force production.

Additionally, we must discover the best modalities and methods of training that elicit positive adaptation in specific joint actions of the hip, while acknowledging the benefits of properly selected and appropriately loaded exercises that fulfill our need to train the foundational patterns.

OUR GOAL AS PROFESSIONALS IS SIMPLE:

Deliver results to our clients while honoring their individual needs, goals, and abilities. We do this by optimizing exercises, programs, and coaching methods to provide the safest, but biggest, challenge to their system.

Our work as a student, in the proverbial darkness, is what allows us to become the teacher in the light. A tireless commitment to mastery is what allows an artist to become renowned – and in the case of a fitness professional – our science is our art.

MASTERING HIP ANATOMY

The human hip is a highly mobile joint surrounded by two stable joints: the lumbar spine and the knee. This arrangement of skeletal structures allows for tremendous force production potential in a wide variety of positions. The bilateral squat stance, bilateral hinge stance, and even unilateral knee-dominant positions can be loaded and trained through large ranges of motion safely.

The key for most clients is to unlock their hips from the lumbar spine by mastering anterior and posterior pelvic tilts as well as the 6 motions of the femur. In addition, mastering Pillar bracing, strong foot and ankle position, and full body irradiation enhances stability and force output potential.

For us fitness professionals, we must first understand the anatomical design of the hip, the lumbar spine, and even the knee joint to optimize hip function. Excellence derives from knowing how to brace the pillar complex, drive tension through the ground, and troubleshoot biomechanical shortcomings in a client’s patterns.

In this section, we will explore the bone and joint anatomy of the hip, knee and lumbar spine while also looking at the various muscles that function in the Lumbo-Pelvic region. Then we will explore the interrelationships with our Pillar complex and feet and the effect of irradiation and the synergistic spiral effect on hip function.

Two skeletal structures and a ball-in-socket joint provide the framework for which dozens of muscles pull upon to create movement.

BONES AND JOINTS

When simply viewing authentic hip anatomy you must only consider two skeletal structures: the pelvis and the femur. Both bones are large, weight-bearing structures capable of supporting significant force production. Together they meet at the femoral acetabular junction – a ball and socket joint that has access to 3 degrees of freedom while in centration.

However, when looking at hip function, we must also include the lumbar spine and sacrum as well as the knee joint as their relationship to the authentic hip is impossible to separate in compound and foundation training patterns. A squat, deadlift, or lunge, specifically, requires varying degrees of action, or resistance to action, from all the joints involved.

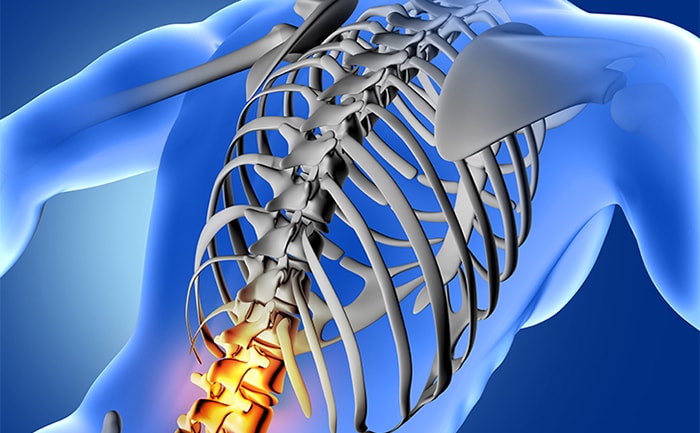

Fig 1.1. – Skeletal Structures of the Hip and Surrounding Areas

The Pelvis – The large, bowl-like structure that connects our torso to our legs. Effectively two separate sides of a bowl fused together by the pubic symphysis in the front and the sacroiliac in the back.

The Femur – The longest and most dense bone in the entire human body connects the pelvis, via the femoral-acetabular junction, to the knee, where it meets the fibula and tibia.

The Lumbar Spine – The largest vertebrae capable of withstanding high amounts of force in most positions. Functionally optimally when supported by internal bracing via muscular tension and air pressure in the thoracic cavity.

The Sacrum – The fusion of 5 vertebrae that terminates with the coccyx. Relatively low movement capacity compared to other bones in the body but is the integral link between the pelvis and the lumbar spine via the S.I. joint. Predominantly responds to lumbar flexion/extension and anterior/posterior pelvic tilts.

There are also multiple joints in play beyond the hip itself as the interrelationship between these joints is what creates foundational human movement patterns. Machines and specifically arranged equipment can help isolate specific joint functions, but the for the purpose of this article we are viewing the entire picture:

Femoral Acetabular Junction – The actual hip joint is the ball-in-socket meeting point for the femur and pelvis. There are 6 actions that are possible at this joint:

Fig 1.2 – Joint Action of the Hip

Flexion – Moving the Femur Anterior/Superior to decrease the joint angle in anterior aspect of the hip

Extension – Moving the Femur Inferior/Posterior to increase joint angle in anterior aspect of the hip

Abduction – Moving the Femur laterally in the Frontal Plane

Adduction – Moving the Femur medially in the Frontal Plane

Horizontal Abduction – Moving the Femur Laterally in the Transverse Plane with Knee at 90 degrees

Horizontal Abduction – Moving the Femur medially in the Transverse Plane with Knee at 90 Degrees

External Rotation – In-position rotation of the Femur away from midline within the hip joint

Internal Rotation – In-position rotation of the femur towards the midline within the hip joint

Sacroiliac Joint – Where the Sacrum meets the iliac crest of the pelvis. Initiates the pelvic tilts:

Fig 1.3 – Pelvic Tilts

Anterior Tilt – Rotating the anterior/superior aspect of the pelvis forward and downward

Posterior Tilt – Rotating the anterior/superior aspect of the pelvis upward and backwards

Lateral Tilt – Rotating a single side of the pelvis outward and downward in the frontal plane

Lumbar Joints – Each of the 5 vertebrae are capable of flexing, extending, and rotating on top of another as well as synergistically as a unit. Most importantly, proper core bracing will actively stabilize the lumbar spine during foundational movement patterns. This is especially important for loaded movement.

Fig 1.4: Acceptable Range of Motion at the Lumbar Spine

Flexion: 40-50 degrees

Extension: 15-20 degrees

Rotation: 5 degrees

Lateral Flexion: 15-20 degrees

Knee Joint – The knee joint, where the femur meets the tibia and fibula, is a simple hinge joint that flexes and extends in relationship to the hip and ankle’s position in space. This stable joint provides the foundation for which powerful contraction of the hip and knee flexor/extensors can fire.

JOINT BY JOINT RELATIONSHIPS

The femur’s position is influenced by pelvic tilt. For example, a standard hip hinge involves anterior tilt of the pelvis in addition to flexion of the femur within the joint. Depending upon positional variance – abduction and external rotation could also be present.

In addition, the position of the femur in the hip impacts the position of the knee below it, and as such, requires proper positioning of the ankle joint to maintain healthy knee-tracking. Peak force production comes from centration of the femur inside the acetabular junction of the pelvis.

Lastly, there is tremendous variation in the bone structure at the pelvis and femur between individuals. For that reason, we can expect tremendous variation in squat and hinge position. For this reason, squat and hinge patterns should always be screened, and occasionally assessed, to ensure our clients are in the best position for their structure.

The bones cannot be adjusted and serve as the scaffolding for which all muscles and tendons act upon. We must respect the skeletal design (bone length and girth) and joint anatomy (joint size and depth) to put clients in optimal positions for performance and longevity.

Still, we must also understand the interactions of the muscles of the hip in order to better program exercises and foundational patterns into our client’s lives.

MUSCULAR ANATOMY OF THE HIP

The hip has dozens of muscles that function to move and stabilize the femur and pelvis in space. These muscles run the length of the femur or connect the pelvis back to the lumbar spine. Each of these muscles have distinct functions while also acting synergistically with other muscles as contributors to other motions (for example: the glutes).

In addition to this shared function at the hip, many muscles within the region function at the lumbo-pelvic junction as well as the knee. Some contract to initiate motion while others function isometrically to stabilize these areas vs. internal and external forces.

When viewing the muscular anatomy of the hip complex we can categorize all of the major players into 4 specific categories*:

Fig 1.5 – Muscles of the Hip Complex

Hip Flexors – Quadriceps Group (Rectus Femoris, Vastus Lateralis, Intermedius, and Medialis Obliques), Gracilis, Sartorius and Pectineus, Tensor Fascia Latae, Psoas Major, Rectus Abdominis

Hip Extensors – Hamstrings Group (Biceps Femoris, Semimembranosus, Semitendinosus), Gluteus Maximus, Erector Spinae (Anterior Tilt of Pelvis to allow for greater extension)

Hip Abductors/External Rotators – Glute Group (Glute Maximus, Glute Minimus, Glute Medius), Piriformis (Functions as Horizonal Abductor), Tensor Fascia Latae (Hip Abduction), “The Deep 6” Rotators (Gemelli and Obturator groups)

Hip Adductors/Internal Rotators – Adductor Group (Longus, Brevis, Magnus) – Also contributes to Hip Flexion, Tensor Fascia Latae (Internal Rotation)

*Other intrinsic muscles do function at the hip and spine, but for the purposes of this article we are omitting them since most fitness professionals do not possess the scope to work so deep in the body.

All the muscles are active in every deadlift, squat, and lunge pattern. Moreover, their activity is positionally dependent – meaning a sumo deadlift or skier squat utilizes different muscles in different percentages for force production and joint stabilization.

Understanding this concept demonstrates the need to ensure that positional variety is found in programs, even those that have specific goals (such as hypertrophy or strength). We can train any pattern with intensity and frequency if it matters for output (such as a powerlifting meet), but we should always include variations that balance the training stimuli across a variety of tissues.

Even deeper, we must consider the skeletal anatomy of the individuals we train and understand that we should invest more programming into successful, centrated positions for their body. Doing so will enhance performance and safety in the long-term while omitting the benefits from other, less-optimal positions. For that reason, we always program variations in low doses that allow for positive adaptation to take place in new positions.

Examples: A powerlifter who pulls sumo competitively will benefit from some conventional Hex Bar work at higher loads as well as pure-hinge movements such as the top-down Romanian Deadlift.

A CrossFit competitor who regularly snatches and jerks would benefit from kneeling, upside-down Kettlebell pressing to return the shoulder to its most centrated position.

APPLICATION OF FUNCTIONAL HIP ANATOMY

When looking at the many muscles listed above, and acknowledging that even more intrinsic muscles exist, we can declare that the hip is truly complex. The spiral nature of many of the muscles give them multiple functions depending upon the femur’s position within the hip.

For this reason, we are once again less concerned with knowing the function of each individual muscle group and instead emphasizing our understanding of the movement capacity and which regions of the body drive it.

Understanding what muscles drive a hinge, a squat, a lateral lunge, or our running form allow us to better design training programs to elicit positive results.

From a force production perspective, the spine and hip are necessary elements of the human foundation that allows for muscles to contract with peak force. Our comprehension of their anatomy and function only furthers our ability to properly align the bones, centrate joints, and recruit appropriate musculature in life, training, and sport.

The unification of these segments is also reliant on the effect of muscular tension on the body, via irradiation and synergistic spiral effects.

Irradiation – tension in one region of the body creates tension in neighboring regions. If done properly, a tightly balled fist can lead to tension in the feet and ankles or vice versa.

Synergistic Spiral Effect – The body communicates through a variety of contralateral slings (of both muscle and fascia). This communication is what allows for complex human movement to occur unilaterally and for unification of force production bilaterally. In effect, the right hand can directly impact the left foot and vice versa.

Practice

Stand tall and flex your right fist. Now tighten your right upper arm, pec and lat. Now, brace your core. Squeeze your left glute and turn on those adductors, push the left big toe down into the ground and rotate the floor.

Feel that?

You have utilized both irradiation and synergistic spiral to impact performance.

Can you imagine doing this before your next big training session?

How would your clients benefit?

PILLAR BRACING

As the students of the Pain-Free Performance Specialist Certification learn, the Pillar is critical area comprising of the Hips, Shoulders and Core. By locking down the ball-in-socket joints with muscular tension and using both air pressure and muscular contraction to brace the core – the human body is better prepared to produce, reduce, or transduce forces.

Before detailing the specific training modalities that we can use to target the hips it is important to acknowledge the important function the Pillar brace on all patterns. Whether we are foam rolling, doing a corrective, exercising an accessory pattern, or loading up a primary pattern – we are bracing (to varying degrees) and engaging our Pillar complex.

TRAINING THE HIPS – MODALITIES AND METHODS

It is important to acknowledge that all tools and methods should be available for fitness professionals. We should avoid dogma and single-minded approaches that claim to be fix-all for everything a client would need. Remember, the best fitness professionals do not carry tool belts or toolboxes. Instead, they have access to entire tool shed of equipment, methods, and strategies to get any job done.

Barbells, Hex Bars, Dumbbells and Kettlebells, Iron Maces and Indian Clubs, Yoga Blocks and Foam Rollers, Bands and Cables, Landmines and Machines, and any other implement with verified use is a valid implement for which hip training can be conducted.

Be ready to use everything at your disposal as a coach so that you can always deliver pain-free sessions that put quality training stimuli into your clients and in turn, positively adapt the body.

Find out some of the best ways to train with the Trap Bar Here

EXERCISES FOR THE HIP

With that in mind, there are patterns that work for damn near every person on Earth. When loaded correctly and coached properly – these following exercises are incredible additions to any training program (assuming your client can do them).

We will highlight 4 variations of the foundational movement patterns that are going to work multiple muscles and functions of the hip simultaneously as well as exercises that address the function of the femur inside the femoral acetabular junction.

COMPOUND EFFORTS

FRONT FOOT ELEVATED STEP OVER LUNGES

CROSS BODY 1.5 STANCE DEADLIFTS

TRAP BAR DEADLIFT, RDL ECCENTRIC

Each of these patterns play with different hip positions, transitions, and isometric demands. When used in a program – all these patterns will directly contribute to pain-free performance in the long-term.

HIP ABDUCTION AND EXTERNAL ROTATION

SIDE PLANK HIP THRUSTS

MINI-BAND 45 DEGREE STEP BACKS

Both exercises actively work 3 of the 4 major functions of the glutes, and with conscious contraction into posterior pelvic tilt can go 4/4. This catch-all makes these corrective/activation exercises ideal for feeling the glutes pre-workout or fatiguing them as an accessory at the end of a session.

HIP ADDUCTION AND INTERNAL ROTATION

FOAM ROLLER RDL

FOAM ROLLER GLUTE BRIDGE

Both exercises combine active contraction of the adductors and internal rotators (squeeze and break the block) while actively driving the hip into extension – an unlikely combo that doesn’t lend itself to power or force production, but does improve neuromuscular connections in the pattern – especially in those used to training hinges in external rotated/abducted positions.

HIP FLEXION AND EXTENSION

MINI-BAND HIP FLEXOR/EXTENSION

REVERSE NORDIC CURLS

Both exercises aim to remove the input from external rotation and abduction and focus exclusively on flexion and extension. In the case of the hip flexor lifts – active contraction works the muscles largely responsible for tightening up in squats and lunges and inhibiting fluidity to depth.

Just the same, active contraction of the hamstrings and glutes into extension (without movement) aids in driving joint stability, which for most is the answer to their “hamstring tightness”.

The reverse Nordic curl provides a great “hip” sensation to a knee flexion pattern. An amazing challenge for those trying to work the northern part of the rectus femoris.

CLOSING

Training the human hip is about emphasizing pillar stability in all positions, honoring the skeletal anatomy of each client, and utilizing the correct amount of variation in our corrective, activation, patterning, and training approaches.